Facebook’s Internal Motto Was “Don’t Let the Adults In the Room.” The leadership team routinely dismissed accountability. Governance was seen as a threat to innovation—which became code for doing whatever they wanted.

-

Not long before Carl Sagan died in 1996, I sat next to him at a luncheon in the Hamptons. He was a guest for the weekend, and everyone at the table bombarded him with questions about space, the stars, and other things I don’t even remember. What I do remember is how thoughtful he was, how careful with language, and how human he seemed.

It wasn’t until more than 30 years later that I came across one of his warnings—buried in his 1995 book The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark—and it stopped me cold.

“I have a foreboding of an America in my children’s or grandchildren’s time—when the United States is a service and information economy; when nearly all the key manufacturing industries have slipped away to other countries; when awesome technological powers are in the hands of a very few, and no one representing the public interest can even grasp the issues; when the people have lost the ability to set their own agendas or knowledgeably question those in authority; when, clutching our crystals and nervously consulting our horoscopes, our critical faculties in decline, unable to distinguish between what feels good and what’s true, we slide, almost without noticing, back into superstition and darkness.”

It’s not just prescient, it’s exactly the world we’re living in now. The science and technology he once celebrated as tools for progress have become instruments of power and control. Not because the tools changed, but because the people holding them did.

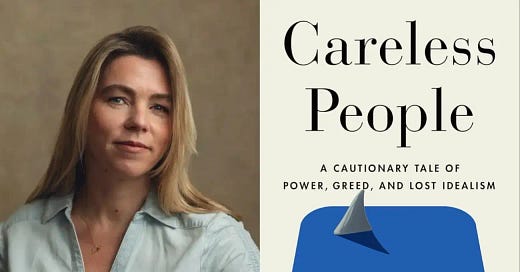

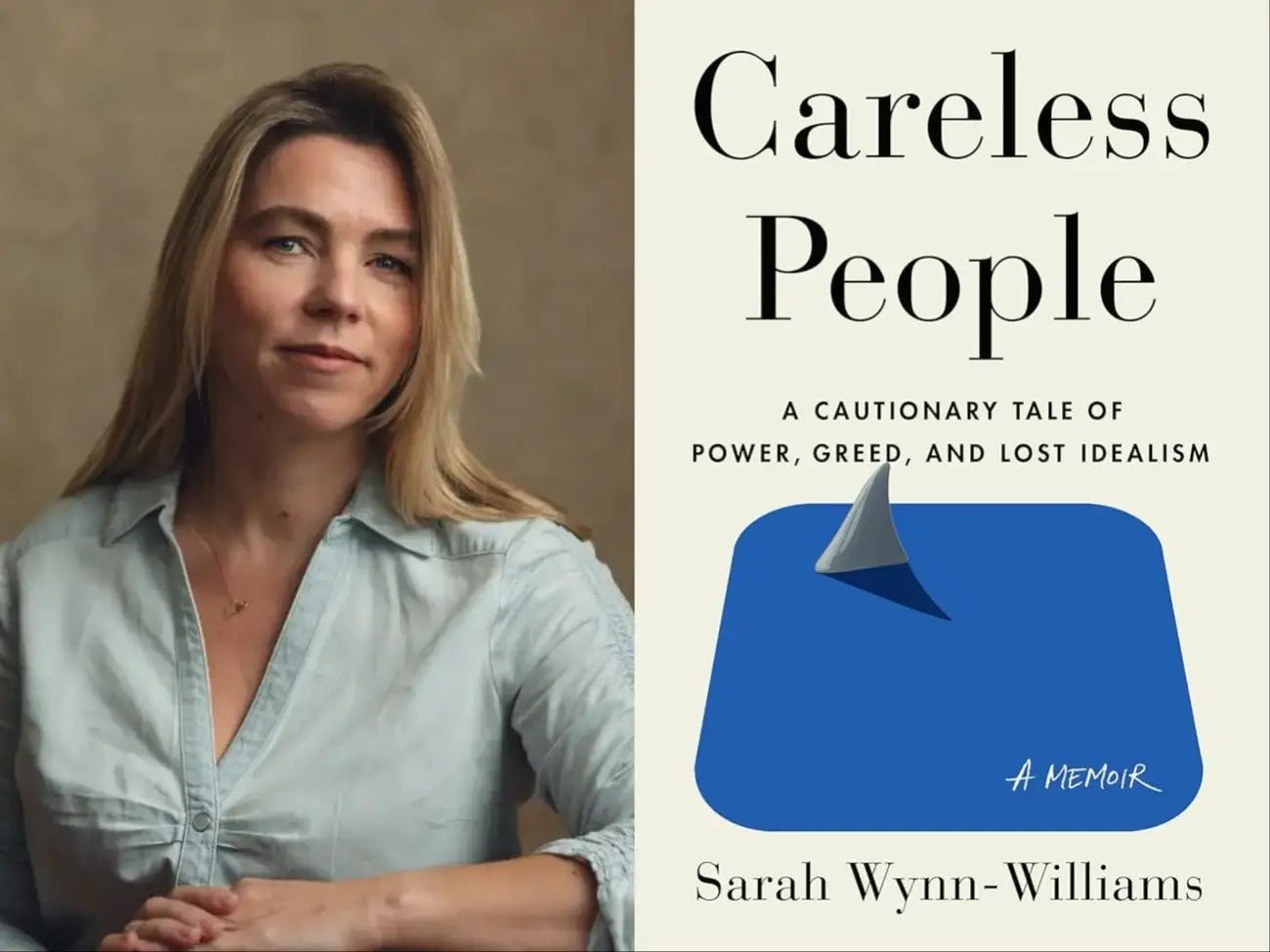

Which brings me to Facebook. And to Sarah Wynn-Williams, who was in the top echelon of Facebook a decade ago before she was ostensibly fired for not passing out the Kool-Aid and reporting sexual harassment in the workplace. Her new book, Careless People: The Misguided Minds Behind Social Media’s Disruption of Democracy, is the most important nonfiction book I’ve read this year—and maybe this decade. OK, maybe even my lifetime.

I read the review in The New York Times. I guess I shouldn’t be surprised. The reviewer didn’t call it the game-changing book of the year, which is exactly what I think it is. I also guess I shouldn’t be surprised that META has tried to stop the book from being distributed but hasn’t sued her for any inaccuracies. They have stopped her from testifying before Congress and from doing interviews, but hey, why would justice protect someone who is not a friend of the present administration? Because the book is likely backed up with emails, documentation, and a level of substantiation that Macmillan wouldn’t dare publish without. Every dotted “i” and period accounted for.

So what surprises me isn’t that META tried to quiet it. It’s that it’s not headlines. It’s on the bestseller list. I get it—we’ve got plenty of things vying for attention in the news cycle—but this book lays out the corruption, the infantilism of Zuckerberg, and something I’ve said for decades: Sheryl Sandberg is a bad human. She’s all persona, no purpose. Also, she’s kind of weird if you believe what the book describes as her sleeping habits.

-

Sheryl Sandberg Built a Culture of Deception and Deflection. From coordinating smear campaigns to shielding Zuckerberg’s worst instincts, Sandberg emerges not as a feminist icon but as a loyal architect of Facebook’s moral collapse.

-

When Sheryl’s book Lean In came out and I was one of the few women who wrote a scathing review of it, I got attacked. All I had was a point of view that was different. I realized then how strong the machinery is. PR. Positioning. The desperate need women feel to support other women at all costs, because sometimes it’s the only path forward in a world that has worked overtime to keep us out.

But how could women read a book that preached about bringing others to the table and not notice that Sandberg was the only woman at Facebook’s board table, aside from the HR rep? It didn’t add up. And people I knew told me stories. Bad ones.

And then when she was exposed for having been the one to begin what turned out to be a lasting attack of lies about George Soros—which was planted and nurtured inside Facebook and became “truth” in the minds of millions, I could not understand how she survived that. The email was there. And, she finally admitted it. It’s addressed in the book. The memo she wrote after hearing Soros’s speech at Davos more than ten years ago—where he described exactly the dangers of Facebook to society, politics, and the future of the world at large—made her put all of Facebook’s resources into diminishing the man rather than standing up to the scrutiny, which turned out to be absolutely right. She’s a bad human. To the core.

But here’s the dealbreaker. Can you believe it’s not Sandberg?

Sarah Wynn-Williams lays out exactly how Trump won in 2016. Facebook employees embedded with the Trump campaign taught them how to manipulate the algorithm, repackage the truth, and get him elected. She was there. She was on the plane when Facebook’s head of policy walked the petulant, angry child that is Zuckerberg through what happened—step by step, fact by fact. He was devastated that the press was blaming him for Hillary’s loss and didn’t realize that it was true.

They showed him the math. They showed him the process. They showed him how Facebook had elected Trump.

And here’s what Wynn-Williams doesn’t say, but I will. Hillary Clinton’s team also got offered help by Facebook. And they rejected it. Just another example of how her decades-long inner circle helped her lose an election that should have been hers. That’s a book for another day. But it’s important because it shows that FB wasn’t routing for DT, they were increasing revenues. The cost to the world be damned. Once they realized that power, they didn’t do the right thing and fix the issues, they doubled down on using it to become the most powerful company in the world. Just like George Soros said in Devos.

If you read one nonfiction book this year to understand why we are where we are—globally, politically, morally—it’s this one. Careless People. From The Great Gatsby? If even half of it is true (and again, I believe it’s all backed up), it paints a picture of how we fell so far but not what it would take to rise again. That will be up to us.

I want to have lunch with Sarah Wynn-Williams. I want to ask her a million questions. She doesn’t entirely take responsibility for her role. She admits she didn’t speak up as much as she should have, but highlights the moments she did speak up. I get that. It reminds me of the early days of the MeToo movement—especially around Harvey Weinstein—when women said they walked out the door rather than comply. I was never so sure about that. It’s hard to admit complicity. It’s even harder to say, “I helped do this. Hold me accountable.”

But God, I’m glad she wrote the book. And I’m so grateful to my friend Patrice Tanaka—CEO of Joyful Planet—who told me to read it. Patrice doesn’t tend to linger on the dark side of the moon with me. She lives in joy. But this book? This book is necessary. I haven’t discussed it with her yet, but I will.

Careless People lays out the blueprint. The scaffolding. The architecture of how these platforms and companies are built—and what we’ll need to understand to dismantle them, which may be our only hope for salvation.

How are they built? By infantile humans with brilliant, untethered minds who can toy with science and math in ways the rest of us can’t fathom. And then they surround themselves with people who, for one reason or another, never learned to choose right over profit.

Ever.

I have to take a little longer to talk about China. That’s the one that’s going to scare the shit out of you.

Zuckerberg was determined to get into China. So what did he give away? He gave away the data of the Chinese people participating on Facebook. He didn’t even do that for his own government in the United States, which would have been against our laws anyway. And yes, China is using that data to further control their population. And Myanmar? People died in Myanmar because of Facebook’s caving to the government in order to be allowed in.

I spend perhaps 80 or 90% of my thinking time focused on Trump’s administration and D.C.’s behavior these days. I think we all do. But what we’re missing is that it’s not just government or politics. It’s everything. It’s science and how we’re corrupting it in the name of profit. It’s corporate power and its ability to do damage while we’re looking the other way. It’s the loss of collaborative communities.

We can’t keep spending all our time on the ridiculous human being in charge of the United States. We have to widen the lens.

And yes, I know. We’re tired. Too bad.

The reason to read Sarah Wynn-Williams’s book is because it gives you an inside picture that helps you understand what other companies are doing. And also, it’s a call to action. I’m not sure we’ll respond. I think the American ability to be disciplined and forward-thinking might’ve peaked in the 1950s. We want what we want at the exact moment we want it.

Will people give up Facebook—something they’re addicted to—after reading what’s behind the firewalls? I doubt it. I make money on Facebook. For my clients. For my company. But the more I know, the harder it is to participate without guilt. Eventually it’s like ice cream, not worth it because of how you feel after.

Did you know book clubs and book groups are a growing phenomenon in America? I believe that women will change this country. This is not a fun book to read in book club. But God, it’s worth it. Please bring it. Suggest everyone reads it. Or divide the book up—three chapters per person—and report back, because who could possibly read the whole thing and not want to stick their head in the oven?

Back to Sarah Wynn-Williams. She was not a good human surrounded by bad ones. I’m not sure anyone, even Zuckerberg, set out to do wrong. But power and money are shiny objects that are not easy to ignore. It’s hard to look in the mirror. And honestly, I don’t know that I would’ve acted differently in her place. And neither do you.

This book is not about sitting in judgment of her. Or even them. That ship has sailed. He’s out there and his minions are now just like DT’s—they will guard their spot on the carpet at all costs.

So it’s about sitting in judgment of ourselves. Because now it’s all laid out before us. The only question is, what will we do about it? I have weaned myself off Amazon. It hasn’t hurt at all, surprisingly. Actually, it’s saving me money, which in this environment is smart. But will I post this missive on Facebook and get a few hundred more reads? That’s the question I have to answer. I will not post this one, but is it because I realize it could jeopardize the positive algorithms I enjoy, or because I have to start somewhere—and now I know they crossed my line in the sand, how can I sleep at night using them?

May I post it on FB?